In recent years both local and national museums have made moves to attract a much wider range of visitors with new models and displays but the Gore District Council gets a special innovation award for selling its own moonshine to visitors.

The council is building a new Arts and Heritage Centre to house the local district museum and research centre, plus an internationally renowned art gallery, and the already popular Hokonui Moonshine Museum. The project is costing about $200,000 and was funded by the Provincial Growth Fund.

As Jim Geddes, curator of the Gore Arts and Heritage Precinct, says; “It’s going to attract people who want to come and see something which is not your normal distillery.”

This museum, which opened two decades ago, celebrates an illegal period in the local district when it was the centre for the distillation and supply of locally made whisky. The Gore District Council has a license to distil this famous moonshine which, in the new centre, will be made to a traditional in new custom-made still made by Rivet Engineering of New Plymouth.

The still has been designed by Steve Nally from Invercargill who says it is based on the old pots the moonshiners made in the area.

“What we’ve built is a pot still, instead of column stills, or other forms of stills, because of the Scottish heritage involved. Scottish whiskey makers used pot stills traditionally.”

The still has a distilling capacity of 500 litres and a four-hour trial run proved the product “quite exceptional”, he adds.

The Hokonui whisky story leads back to one family, the McRaes. After almost a century as criminals, Southland’s most famous whisky producers have emerged as folk heroes. Its story is told in Gore’s Hokonui Moonshine Museum and celebrated each year with a food and whisky festival.

The family settled in the Hokonui Hills, near Gore in the 1870s complete with a pot from home at a time when most whiskey was imported and watered down and local production heavy regulated and taxed under the British colony laws of the time.

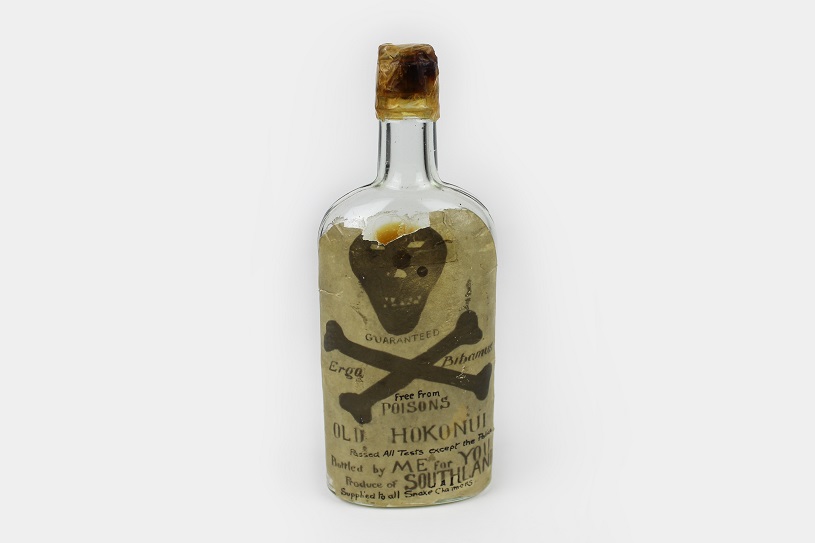

To the McRaes, undercover whisky-distilling was second nature and they hid their still in the creeks and gullies of the Hokonui Hills and selling it quietly to locals in bottles, cans and milk billies.

The still has a distilling capacity of 500 litres and a four-hour trial run proved the product “quite exceptional”

Jim Geddes says there were two types of Hokonui whisky: the old Hokonui – the high-quality product of the McRae clan – and the substandard spirit produced in rudimentary stills, often constructed from 44-gallon drums.

“For the old McRaes it was a cultural thing. It was something that had been passed down by their ancestors. For others, it was purely a money-making thing. Some people deliberately flouted the law, but the old McRaes didn’t. It wasn’t so much that the McRaes were out of step with the law as the law was out of step with them.”

Hokonui became highly sought-after by the region’s drinkers, and the moonshiners became highly sought-after by the law. There are many stories of law evasion in the Hokonui Hills. One officer stationed himself outside the McRae home, hoping to overhear details of the secret distilling locations. But the family spoke Gaelic at home and the officer retreated none the wiser. Another story concerns a visit to Mary McRae from an Invercargill constable. Mary is said to have hidden a barrel of whisky under her full skirts. On yet another occasion, police arrived to find the aging Mary in bed. What they didn’t find were the stoneware jars of whisky her sons had hurriedly put under the blankets with her a few seconds before.

Hugh Sherwood Cordery was the collector of customs in Invercargill between 1928 and 1935. A teetotaller, he made prosecuting illegal distillers, particularly those producing dangerous brews, his personal mission. He pioneered the use of an aircraft to find stills and took along his own box Brownie camera to record his findings. Yet he occasionally struggled to secure prosecutions with Southland juries reluctant to convict McRaes. He succeeded in driving a small number of errant distillers from the district, but most of those who were convicted paid their fines and returned to their farms.

The last prosecution for illegal distilling was in 1957. Gerald “The Major” Enright of Timpanys near Invercargill had a huge illegal distribution network that stretched from Invercargill to Christchurch. In 1950 he had been caught and fined and his distilling equipment seized. The police didn’t destroy the still, however, but sold off the components at an auction house in Invercargill. Enright’s friends were the successful bidders. When he was caught again, he was charged not only with illegal distilling but also with using seized equipment. This time his punishment carried a jail sentence (home distilling became legal 1989).

The history of such prosecutions are on display at the Hokonui Moonshine Museum in Gore, thanks in part to Cordery’s grandson, Sherwood Young, a police historian in Wellington who donated images from his grandfather’s personal collection.

“There was no material in any local archives that related to Hokonui.

We had to start from scratch,”: he says. “The Distillation Act had only been officially relaxed a few years earlier so people were still a bit reluctant to talk about it. We had to tread very carefully.”

One of this country’s leading heritage officers, Sue Wilson, spent four years collecting information for the museum. She started with official records of prosecutions at Archives New Zealand and then worked with police, customs and temperance groups. She tracked down descendants of Mary McRae and recorded the stories of old-timers who had been around during the moonshine era.

Together, Sue Wilson and Jim Geddes fleshed out the history of Hokonui, converting an oral collection of myths and tall tales into a full and factual record.