MMP was expected to break the old Parliamentary duopoly of National and Labour and lead to far more inclusive and diverse political debate. By Peter Dunne.

Indeed, the increase in the number of parties in Parliament has spread the range of views being heard in the House, but it is doubtful that this has led to a greater level of debate about those views.

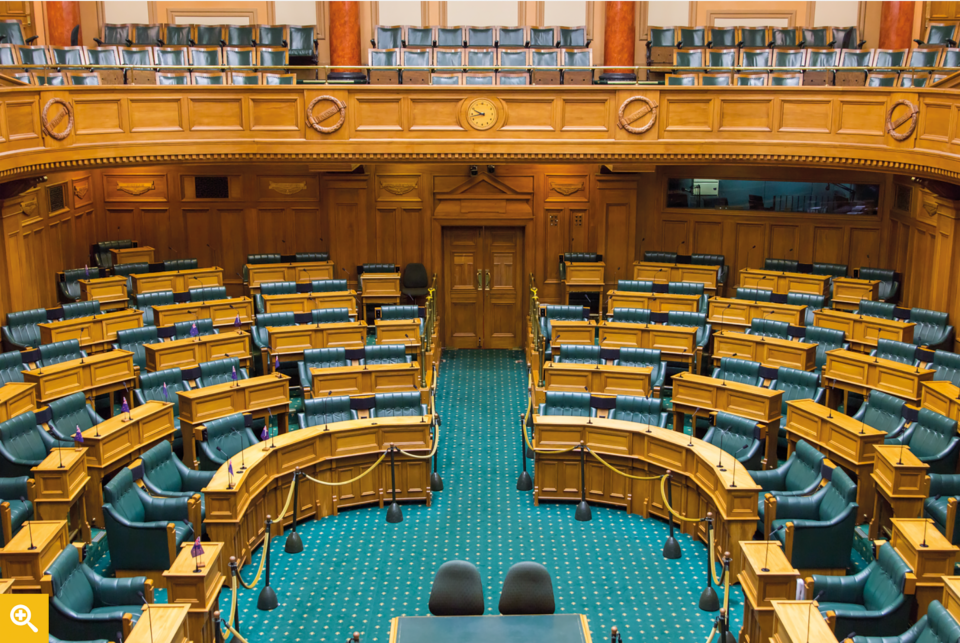

Contrary to what some might imagine, Parliamentary debates are not free-ranging expressions of opinion, where differing ideas and policies are contested. They are highly regimented. Most debates are time limited, with speaking times (10 minutes per speaker) and speaking order pre-determined and distributed evenly between the government and opposition sides of the House. A typical debate comprises 12 speeches, with each of the six parties currently in the House getting at least one call.

Debates have therefore become occasions to state party positions, rather than to contest differing ideas. Consequently, MPs often appear to be no more than the delegates of their respective party when speaking in the House, rather than legislators debating the merits of specific legislation.

In short, contemporary political debate has become all about political parties rehearsing established political opinions to their respective political audiences, rather than debating new ideas and seeking to reach consensus about the best way forward.

The same tactic also applies to the broader approach most parties take in promoting their interests. In this respect, it is worth recalling Hillary Clinton’s observation that good political stories always contain a “goodie” and a “baddie”. So, when the parties tell their stories to their supporters, they are always the “goodie” identifying the “baddie” they are fighting to protect the country from, and this is given as the reason why people should vote for them.

The recent spat between NZ First leader Winston Peters and Green MP Ricardo Menendez March is a case in point. The row is less about Menendez March’s use of ‘Aotearoa’ to describe New Zealand than it is about asserting the respective brands of NZ First and the Green Party.

To traditionalist, anti-multicultural NZ First, the very presence in Parliament of Mexican immigrant Menendez March is bad enough, but his reference to Aotearoa instead of New Zealand was wokeness in the extreme. Peters’ comments were therefore a dog-whistle. The obverse applies in the case of the Green Party. To them, Menendez March was showing respect to tangata whenua [Maori] by referring to New Zealand as ‘Aotearoa’ and acknowledging their traditional rights and role [see editor’s note].

But neither NZ First nor the Green Party has any genuine interest in debating their respective positions with each other – the far more critical point for both was to window dress where they stood for the benefit of their supporters.

The same goes for ACT and Te Pati Maori in their dispute over the Treaty Principles Bill. Each desperately needs to be able to portray the other as intolerant, unreasonable and anti-democratic to validate its own position and strengthen its appeal to its core supporters.

Again, it is less about reasoned debate of differing points of view than an absolute statement of an unshakeable position. The last thing they seek or want is any form of compromise or reasoned discussion.

This sharpening political fundamentalism is creating a complex problem for both National and Labour; more traditionally broad churches than narrow lines of opinion. It is more acute for National at present, simply because it is the leading party of the government.

Prime Minister Luxon often looks hamstrung by the extreme or unreasonable positions of his support partners. While he cannot endorse them, because they are not what his party stands for, he cannot reject them outright either, because that would destroy his coalition Government. But pretending the differences are not there at all, as Luxon often appears to do, is the worst position of all. It leaves the Government looking weak and indecisive.

Therefore, to resolve this dilemma, National needs to better develop its own political story, complete with its own “goodies” and “baddies”, instead of just hoping, as currently appears to be the case, that its tick-box list of achievements will carry the day.

It is a smaller but similar problem for Labour at present. However, it will grow as the election nears and more attention is paid to the radical policies of the Green Party and Te Pati Maori and how they might be accommodated in a future Labour-led government. Opposition leader Hipkins is frequently critical of Prime Minister Luxon’s current difficulties, seemingly unrealising that precisely the same challenges are lurking just around the corner for him in the run-up to the election.

The demise of political debate as it used to be, in favour of the fervent, dogmatic statement of party opinion as incontrovertible fact, as we have now, has dramatically changed the nature of political discourse around the world.

The absolutist way the Trump Administration and its allies operate is the obvious extreme example. But, our political system is not immune from these features. The redefinition here, of political debate to be less about the exchange of ideas than the statement of pre-determined positions, should be viewed with increasing concern rather than becoming accepted the way it seems to be.

Over 50 years ago, the satirical television show Monty Python’s Flying Circus attacked the, then-emerging, lowest-common-denominator approach to resolving complex issues in a skit where the existence of God was decided in a wrestling match by two falls to a submission.

Sadly, that is precisely the same approach we are taking to complex political issues today.

Editorial note: Aotearoa was a name associated with the North Island, not the South Island, and has probably become popular because of the National Anthem. The literal te reo Maori translation of New Zealand is Nu Tirani – as is written in the Maori version of the 1840 Treaty.