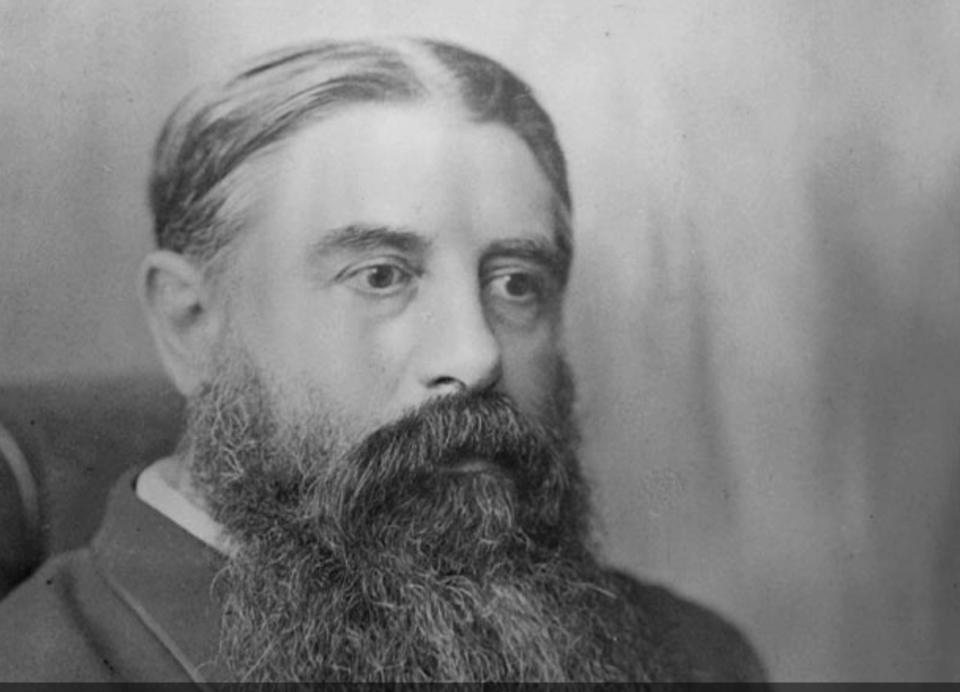

Image: Julius Vogel

After decades of the central government dictating to local councils under the 1989 and 2002 Local Government Acts, local authorities have danced between ‘reforms’ every time there’s a change of government. By Alan Titchall.

The current Government has gone a step further and suggested scrapping all 11 regional councils under its RMA reforms and telling the rest that they are a barrier to the country’s growth and will be ‘overruled’ if the central Government decides that their decisions negatively impact economic growth, development, or employment!

‘Reform’ towards centralist control should be no surprise to a country of a meagre five million (less than a city such as Melbourne) run by 123 members of Parliament representing six political parties and a full-time bureaucratic army almost 70,000 strong. Even Prime Minister Christopher Luxon has recently conceded to media sources that there are too many layers of government here, which drives excessive bureaucracy.

However, we have always been an over-governed country, a legacy that dates back to our foundation when the British took the initial steps to turn these lands into one of its colonies.

First, it had to subjugate the original settlers from East Polynesia (Maori), the Europeans who had already established settlements here, and the competing French-backed colonists eyeing the South Island. These days, the historic narrative is that our country was founded in February 1840 with a hongi and a handshake at Waitangi over a Treaty.

Nah, it was way more complicated than that. The ‘Treaty scenario’ is a typical way Kiwis look back at history and world affairs, often relying on overly simplistic and digestible soundbites that overlook their complexities. As Leslie Hartley’s famous first line in his novel The Go-Between says, ‘The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there’.

First, 19th-century treaties were made between sovereign countries. There was no paramount tribe that could answer for the others in 1840 and still isn’t. The three clauses of the Treaty were written by non-lawyers with the ‘Tangata Maori’ version in a written language that had only been designed at Cambridge University in the UK less than a decade before. How many people at the time could read when even a large percentage of the European settlers were illiterate and signed deeds with an ‘X’? Mandated schooling for (European) kids was still 37 years away.

After the ceremony at Waitangi, the British representative charged with the colonisation of this country, Lieutenant-Governor Capt. Bill Hobson, would have to wait at least eight months for any Treaty signatures to return from other, isolated parts of the undeveloped country. While waiting, he suddenly faced unpredictable and serious challenges.

Around May 1840, Hobson got wind that the French Government had sent immigrant ships down here with a navy escort to settle in the South Island. He sent HMS Britomart to Akaroa, Banks Peninsula, with police magistrates, a week before a shipload of French and German colonists landed there. The captain of Britomart, Owen Stanley, had raised the Union Jack to emphasise the United Kingdom’s claim to sovereignty over the area, as Hobson on 21 May 1840 (without the final Treaty signatures) declared sovereignty over the North Island by ‘cession’ and the South Island by ‘right of discovery’.

That was his first challenge over. Now he faced rebellion from the European settlers, many of whom had escaped political and social oppression in Britain and Australia, who had no desire to see the British Crown established here. The historically maligned New Zealand Company, founded in 1825 to ‘colonise’ these lands through private enterprise systems, had merged with Wakefield’s New Zealand Association in 1837 and armed with a Royal Charter from Britain, would prove to be Hobson’s ‘Moriarty’.

By May 1840, the Association was well-established in Wellington (the city having been named after its patron, the Duke of Wellington) and had numerous other settlements in the planning as it recruited immigrants from Europe. It is worth noting here that our modern founding narrative suggests that the British intervened to protect Maori from unfavourable land sales by the New Zealand Company. The second clause of the proposed treaty made it emphatic that all land sales dealings would need to go through the British Crown. However, clipping the real estate ticket was its future income before a taxation system could be introduced. And, of course, any ‘disputes’ between the first European settlers and Maori landowners over real estate before the British took over, paled in comparison to future wars between tribal landowners and the British Colonial government which involved massive confiscations.

The colonial government dropped its pre-emptive rights over land sales from 1844 to 1846, re-established them in 1846 with the Native Land Purchase Ordinance, and then abolished them again in 1862. It was resumed in 1892 and finally removed by the Native Land Act 1909.

Those bloody colonials

While Hobson waited for the treaty signatures, the independent settlement of Wellington had formed a ‘council’ and, in May 1840, talked of an independent ‘republic’.

Solution: Directly after he declared British sovereignty on May 21, Hobson sent a magistrate with armed marines to Wellington to forcibly disband the council, which he considered an attempt at local governance with an ‘illegal and treasonable body’ that conflicted with his authority to levy rates and taxes. By this stage, it was a moot point whether enough Maori tribal representatives had signed his Treaty or not. However, numerous chiefs didn’t, and many tribes in the North Island took exception to British rule and weren’t subjugated until the late 1860s through military action. Some 165 years later, the Crown is still settling the aftermath of that conflict.

New Zealand was established as an independent British Colony by a charter, known as Letters Patent, issued on November 16, 1840, by Queen Victoria, which arguably serves as our founding document. It doesn’t mention a treaty, nor does our first Constitution of 1851, or any other. The Treaty is not mentioned in law until the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975, 135 years later, with increasingly convoluted regulatory interpretations and applications made by successive governments since, particularly under Labour administrations.

Auckland versus New Zealand

Hobson’s novice colonial government’s conflict with the more organised settlers had just begun. He decided to create a capital in Auckland. The problem was a skilled labour shortage. His agents resorted to poaching settlers with trades from Wellington before those skills were recruited from Australia.

Auckland finally opened as one-acre blocks on either side of the Queen Street creek, selling for an average price of 555 pounds per acre — one of the most expensive land sales in the British Empire at the time, and bought mainly by overseas speculators. Auckland is still one of the world’s least affordable cities.

As the Colonial Government’s Auckland settlement filled with new immigrants (mainly from Australia), there was no love lost between it and others around the country, and the battle over central and local governance lasted for many decades.

This included a mighty central-local government clash in the 1870s between Julius Vogel, the Colonial Treasurer, and the locally governed provinces. This was mainly due to his ambitious public works and immigration policies, particularly his proposal to use provincial land as collateral for huge overseas loans.

This led to the abolition of the provinces in 1876, before the country slipped into its first depression in the 1880s, blamed on Vogel’s overambitious borrowing. When provinces were abolished, the central government assumed responsibility for local governance. Rural areas were divided into counties, while towns were divided into boroughs, with special-purpose authorities administering services such as health, education, river control, and water supply. By 1912, there were about 4000 territorial authorities of various kinds. It was a bureaucratic nightmare (or not) that largely persisted until the 1989 reforms, when 850 administrative organisations were consolidated into 86 local authorities.

These authorities were restructured so that a non-elected chief executive was responsible for employing staff and managing operations, and commercial and non-commercial activities were separated.

And, here we go again, with the Coalition Government RMA and local government reforms. Not much has changed in terms of a political legacy involving a power struggle between the Crown and the rest of the country over land, regulations, social license, and even sovereignty.

It’s the way we are. It might be a nice place if we ever get there.

Hei mauri ora.

A legacy of provincial-central conflict

Julius Vogel instigated one of our first major punch-ups between Wellington and regional government at a time when nine self-governing provinces ruled the colony. As Colonial Treasurer between 1869 and 1876, Vogel was initially supportive of provincial control of colonisation and development. When the provinces objected to his massive public works scheme based on huge overseas borrowing using their land as collateral, he got rid of them. They were replaced with a tamer system of counties, later reorganised into district and city councils within larger regions that existed until the major local government reforms of 1989.