Minister for the Environment, David Parker spoke at the LGNZ conference in July on governance and decision-making in the Labour Party’s proposed RMA reform. He insists local government will continue to be the key institution, shaping and implementing the new system and it is not a 50/50 co-governance model between the Crown and Maori tribes, yet went on at length to explain how ‘Maori’ will play a more “effective” role in future plan-making.

“There is a broad consensus that after 30 years as our cornerstone environmental and The Infrastructure Commission recently reported that the costs of consents for medium sized infrastructure projects have increased 150 percent in the last 10 years,” he said recapping the reason behind the reforms.

“Costs are 250 percent of what they were a decade ago. Elected mayors, councillors, private sector interests, ENGOs and all of us are frustrated with the RMA. Reforming the resource management system is a priority and we have committed to repealing the Resource Management Act and enacting the Natural and Built Environments Act and Spatial Planning Act this parliamentary term.

“We are following the Randerson Report closely. I sent a full copy of the Randerson report to every mayor, councillor and iwi authority and campaigned to implement it. The Randerson report involved extensive consultation and built on earlier work by the Productivity Commission, Local Government New Zealand, the Property Council, Infrastructure NZ, the EMA and the Environmental Defence Society among others.

“The Spatial Planning Act, provides for a mandatory spatial plan across all regions. We acknowledge those councils that have been doing non-statutory spatial planning already – we have learned from them in preparing this legislation.”

Parker said the Government is set to introduce both pieces of legislation to Parliament in October following on from the Select Committee Inquiry into the Exposure Draft in 2021.

The Spatial Planning Act (the SPA) will enable long-term spatial planning at the regional level through the development of Regional Spatial Strategies, he says.

“The Natural and Built Environments Act (the NBA) will be the primary piece of legislation to replace the Resource Management Act (the RMA). Like the RMA, the NBA will be an integrated statute for land use and environmental protection.

“We did consider separate development and environment Acts, but concluded that did not resolve the tension between the two objects. A key element of this legislation is the National Planning Framework which will give consistent national direction.

“The NPF will include an infrastructure chapter which will provide much-needed direction to regions on how to plan for and enable infrastructure in the Regional Spatial Strategies and Natural and Built Environment Act plans and resolve conflicts that arise.

“The infrastructure chapter is expected to incorporate by reference a suite of nationally-consistent planning and technical standards for infrastructure that should be used in all plans and for consenting decisions.

“For example, the chapter may list standards for erosion and sediment control. Councils will state which standard must be used but the need to have bespoke conditions in applications and consents will be avoided. The Infrastructure Commission is leading the work on this new infrastructure chapter to ensure it is robust and workable.

“This will build on the Government’s other moves to accelerate housing provision, and the infrastructure that supports it.”

NBA Plans will be given direction by the National Planning Framework and Regional Spatial Strategies, he says.

“NBA plans will replace current RMA plans and cover both resource allocation and land use for a region. We want to ‘front load’ the system to reduce the need for consents. A more robust and rigorous compliance monitoring and enforcement system will include new civil enforcement options used overseas.”

Local government will continue to be the key institution, shaping and implementing the new system, he says.

“We are not proposing a 50/50 co-governance model, but we are including a more effective role for Maori and central government in plan making processes. In her speech to you the Prime Minister noted that it is her job to ensure that local government is supported, and that when it’s a joint challenge, that you have a partner in central government.

“As the reforms progress, and we change our focus onto transition and implementation I want to reassure you that you will continue to have a partner in central government. I welcome your advice and feedback, and remain open to discussing these reforms at mayoral forums across New Zealand.”

“I have found the advice given by the Local Government Steering Group invaluable. The Steering Group has tested our thinking about how the regional planning committees will work in practice, and the accountability that needs to go with this. They have also been critical in identifying mechanisms to ensure local voice is upheld in the regional planning process.

“As a result of their suggestions I think we have a more robust governance framework in a number of areas. I want to acknowledge the amount of time the steering group has spent on this work. I also want to acknowledge the broader local government sector and the ongoing work to implement other reform programmes of this government such as on water and housing.

“I particularly want to thank Mayor Toby Adams, the chair of the Steering Group as his leadership has assisted the Steering Group in providing their advice. He has devoted a significant amount of his time to discussing the reforms with the wider local government sector which I know local government and central government appreciate.”

Moving to a regional planning approach and new governance model

The Randerson Panel recommended a regional approach to spatial and regulatory planning and considered this would both support efficient integrated management by consolidating the number of planning documents and improving their quality, says Parker.

“Over 100 regional policy statements and regional and district plans will be consolidated into around 14 NBA plans. The Panel also recommended a new decision-making model to support the collaborative approach needed.

“In designing this new model, our intent has been to provide structures for joint decision-making. It was not our intent, nor was it in our scope, to reform local government.

“The new legislation will establish a regional planning committee in each region. We know that there is significant variation across the regions of New Zealand and a key design consideration was providing as much flexibility as possible to allow regions to work out arrangements that would best suit them.

“The regional planning committees, who will make decisions on the RSS and NBA plan for each region, will include representatives from all local authorities in the region and representatives of Maori groups in a region.

“When making decisions on Regional Spatial Strategies, the regional planning committees will have a representative from central government. The role of the central government representative will be to corral the multitude of central government agencies (eg NZTA and Kainga Ora) to engage in the process. The committees will be established under the SPA and NBA and be autonomous in their decision-making.

“While the expert panel did not specify how committee composition would be agreed, or how committees would be formed, it pointed out that the number of local authorities and mana whenua mean some regions may want to keep the body to a practical size.

“There will be flexibility on how these committees are formed. As a quick aside, this is an example of how, in drafting these two Bills, we have opted for a less prescriptive approach, especially where this will help to reflect local variation.

“We have set some requirements on the composition of, and number of representatives on regional planning committees. We have decided that the minimum number of representatives will be six, and the minimum number of people representing Maori groups will be two. “Regions will then be able to determine whether they want more than six representatives on the regional planning committee, and whether they want more than two people representing Maori groups.

“We have set the minimum number of committee members at six as it would allow regions with the smallest number of local authorities (Northland, West Coast and Southland where there is one regional council and three district councils) to have, at a minimum, direct representation of all four local authorities and the two Maori representatives.

“The legislation will include considerations to help local authorities and Maori through a process, to come to agreement on committee membership. There will be statutory deadlines. If the parties can’t reach agreement, the Local Government Commission will run a process to ensure committees are established.”

Parker adds that these Governance arrangements will be required to uphold Treaty settlement commitments, where relevant, and Takutai Moana rights. “Existing arrangements under the RMA will also be upheld in the new system. We are carefully considering each of these issues through each Treaty settlement.”

The committees will govern the process of developing and deciding on strategies and plans, and consensus decision-making will be encouraged with committee members expected to work collectively, he says.

“Committees can run some of their processes through sub-committees. While the chair of the committee will play an important role in encouraging consensus decisions, the system will also have backstop majority voting rules. Resolution procedures will be available if the chair determines that a crucial decision (such as approval of a plan) can’t be reached. We expect this to be rare.”

To support committees parker mentioned a ‘host council’ that will provide administrative support such as equipment, ICT and human resources support.

“The host council will not have any greater, or lesser, power, than any other local authority in the region. There will be a secretariat which will provide administrative and technical support, for example plan drafting, policy analysis and coordination of public engagement, sought by committees.

“Again, we are not going to prescribe a particular model for the secretariat – this is for the region to work through. We see secretariats working in a flexible way to take into account the diversity of regions and different preferences for working arrangements. While not prescribed it will make common sense for most secretarial staff to be seconded from councils. Some will work at the secretariat and other will work for their home council.”

Local Government – role and functions

Parker says the Panel did not go into detail about how the committees would be established or work in practice.

“This is another area where we have relied strongly on the work of the Steering Group, the exposure draft process, and submissions from key stakeholders earlier this year on the discussion document. As the key institution in the new system, local government will continue to have critical roles. Some I have already mentioned. Councils will agree on their membership of regional planning committees and make appointments.

“Local government will contribute to RSS and NBA plan development and will continue to have significant responsibilities in helping draft the plans, working with the secretariat.

Local place-making will be part of the plan-development process. This could be through local plans, such as those developed under the Local Government Act 2002. Town centre plans, local community plans and structure plans come to mind.”

Parker acknowledged the first recommendation in the LGNZ submission on the NBA Exposure Draft was that local voice must be included in regional plan-making.

“You recommended, and we have agreed, that two bottom-up mechanisms be added in the new system.

“Firstly, Statements of Community Outcomes setting out a district or city’s vision and aspirations and secondly, Statements of Regional Environmental Outcomes. They will be short documents that will be given to regional planning committees covering significant issues that face a region, district, or local community. These Statements, as well as local government representatives on regional planning committees will continue to ensure that local voices are heard in the new system.

“Local government will support community engagement to ensure RSSs and NBA plans reflect local views and priorities. Local authorities will also be responsible for reviewing and providing feedback on draft strategies and plans.

“Local authorities will remain responsible for implementing and administering them. Consenting and compliance monitoring and enforcement will stay with councils.”

New role for Maori representation

Why local government will also need to continue to work with Maori, forming or building on existing relationships, Parker says that in response to concerns from some councils, ministers have directed the list of authorised representative Maori groups currently maintained by Te Puni Kokiri be made ‘complete’ and concedes that “parties need to know who they should deal with.”

Parker also says efficient roles for those Maori groups and Maori membership on regional planning committees, will help to “give effect to the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi”.

“The reforms will recognise Te Ao Maori [Maori academic world view] and matauranga Maori [Maori cultural knowledge as interpreted in the 21st century]. The Secretariat and independent hearing panels will need competency in this regard.

“Elements of the current system will also be brought over, including roles and functions established through Treaty settlements, Takutai Moana [Marine and Coast Area Act 2011] rights and existing natural resource arrangements. Mana Whakahono a Rohe (1) processes, Joint Management Agreements and Transfer of Powers will continue.”

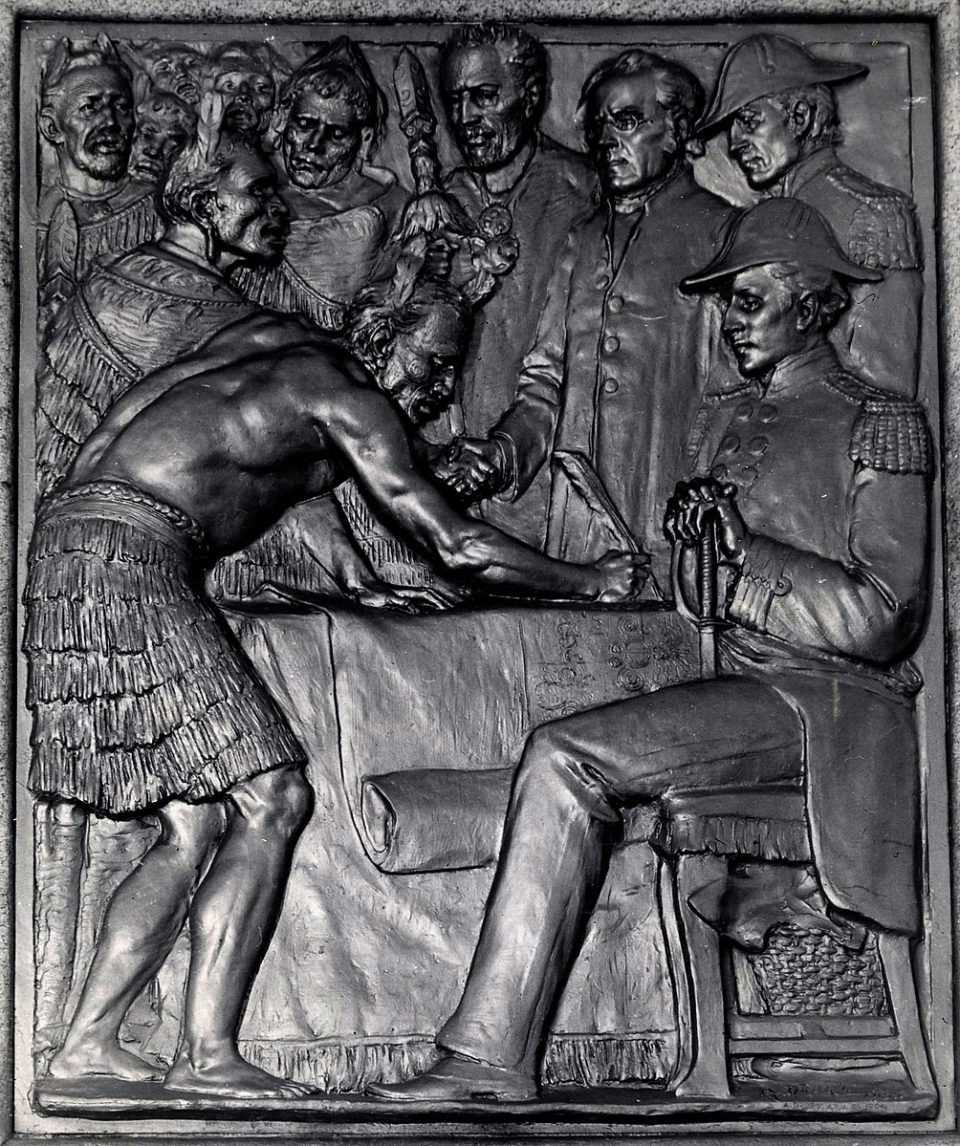

We have adopted the recommendation of the Randerson Panel to establish a new National Māori Entity, which will be an Independent Statutory Authority.

It will have input into the National Planning Framework and have the ability to provide advice to anyone working in the system. It will monitor Te Tiriti [1840 English Treaty of Waitangi between British Crown and some iwi at the time]] performance in the system to assess whether the new system are giving effect to the ‘principles’ of Te Tiriti (2).

“It is intended that Maori will determine membership of the National Maori Entity. Details on how to do this are currently being worked through.”

Role of central government in the new system

Central government will provide oversight of the future system, be responsible for the National Planning Framework, and will play an active role in the development of Regional Spatial Strategies, says Parker.

“As mentioned before the role of the central government representative on the committee making decisions on RSS will be to corral central government agencies to engage with the SPA process and be the “voice” of central government. Having this one touch-point will enable more effective engagement with central government, addressing a frustration of local government that central government can be hard to pin down.

“Central government will have an oversight and stewardship role, alongside independent bodies such as the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment and the proposed national Maori entity.

“There will be reporting every six years to Parliament on the performance of the resource management system and central government will also be required to respond to national reports on the state of the environment and on how the system is working.”

Regarding NBA plans, a key feature will be earlier but less rigid public participation during policy development, says parker.

“This should be an enjoyable part of council democracy for elected representatives and I see no reason to regulate how it will be done. We agree with the Expert Panel that once the regional planning committee agrees to notify their proposed plan, it will refer it to an independent hearings panel to seek submissions, hold hearings and make recommendations to regional planning committees.

“Appeals will be based on the model used for the Auckland Unitary Plan. There will be merits appeals to the Environment Court where the regional planning committee rejects a Panel recommendation, but otherwise appeals are limited to matters of law.”

Transition

“To support implementation, we will work closely with three regions to establish regional planning committees and develop a model Regional Spatial Strategy and NBA plan,” says Parker.

“The goal of the model project is to provide practical templates and lessons for other regions across the country to follow. Plan format will be more uniform making the system easier for users. Digital tools will assist this.

“The May Budget provides $179 million over four years for implementation of resource management reform. This funding ensures completion of the National Planning Framework, the first Regional Spatial Strategies and NBA plans, and funds the National Maori entity.

I believe that inadequate funding for implementing the RMA back in 1992 almost guaranteed its failure. The new system will start with the National Planning Framework, and support for model plans in place. This will put its implementation decades ahead of the inefficient and torturous implementation of the RMA.”

(1) Mana Whakahono a Rohe provisions in the Government’s 2017 amendments to the RMA were designed to provide Maori representation in the RMA processes and decisions and a tool for tribal representatives and local authorities can use to discuss and agree on how they will work together under the RMA, in a way best suiting their local circumstances.

(2) We approached the Ministry for the Environment and asked the question; “Exactly what are the ‘principles’ of the English treaty of 1840 between Queen Victoria and those Maori tribal representatives who actually signed it – as interpreted in the 21st century by the Government, and where can they be officially found?

We found out there is no official definition of those principles (if there is – please let us know). The only answer we got was a reference to the Waitangi Tribunal which uses some ‘core principles’ that have emerged over the years on a case by case basis.

“When inquiring into Maori Treaty claims, the Waitangi Tribunal … each Tribunal panel must determine … which principles should apply to the claims before it”

The Tribunal also goes to pains to point out that it is not a Court and has no jurisdiction to determine issues of law or fact conclusively.

“For this reason, the Waitangi Tribunal does not have a single set of Treaty principles that are to be applied in assessing each claim. Over the years, however, some core principles have emerged from Tribunal reports, which have been applied to the varying circumstances raised by the claims. These principles are often derived not just from the strict terms of the Treaty’s two texts, but also from the surrounding circumstances in which the Treaty agreement was entered into.”