Image: Clifftop and coastal edge development, where the more seaward sections have been down-zoned to limit further intensification in highly exposed areas.

Natural hazard plan changes are being initiated around the country addressing how to incorporate risk-based land use planning to reduce natural hazard risk while while enabling growth, and protecting the environment, mana whenua (cultural land values) and community values, write Richard Reinen-Hamill from Tonkin + Taylor and Mark Tamura from TamuraHill.

Done well, natural hazard, risk-based land use planning can demonstrably reduce natural hazard and climate/weather change risk at community scale, provide certainty and confidence for communities and businesses, and occur over timescales that allow change and adaptation responses to happen at a pace that minimises negative outcomes.

New Zealand practitioners and institutions have promoted risk-based approaches from the early 2010s (Saunders, 2013) reflecting international direction such as the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015) that reinforced the need to prevent new risks, reduce existing ones and strengthen resilience.

Risk-based systems and approaches continue to be promoted, e.g., Natural Hazard Commission (2021), Arnold (2023) and Peart (2023). For coastal hazards there is the long-standing New Zealand Coastal Policy Statement (2010), with versions existing since 1994; and the Guidance for coastal hazards and Climate Change (Ministry for the Environment, 2024), also with earlier versions from 2008.

All of this guidance and direction recognises, in the words of the Natural Hazards Commission, that: “Land use planning may be the most proactive and effective way to reduce the level of natural hazard risk. But it is also a challenging policy area that must balance a range of (sometimes competing priorities) …” (Natural Hazards Commission, 2021, p.6).

More recent work is directly confronting this balancing of competing priorities. Still promoting the use of land use planning to reduce risk, Archie et al (2025) points to the risk of pursuing the natural hazard risk reduction objective too singularly and highlighting the opportunity to enable development where risks are tolerable and benefits are high in order to leverage potential co-benefits and minimise associated trade-offs (Archie 2025).

Recently notified, Auckland Council’s Plan Change 120 (PC120) pursuing the dual objectives of housing intensification and resilience does just this. PC120 proposes further intensification of housing mainly around rapid transit stops, many major bus routes and centres, while introducing an updated risk-based approach to managing coastal erosion, coastal inundation, flooding, landslides and wildfires.

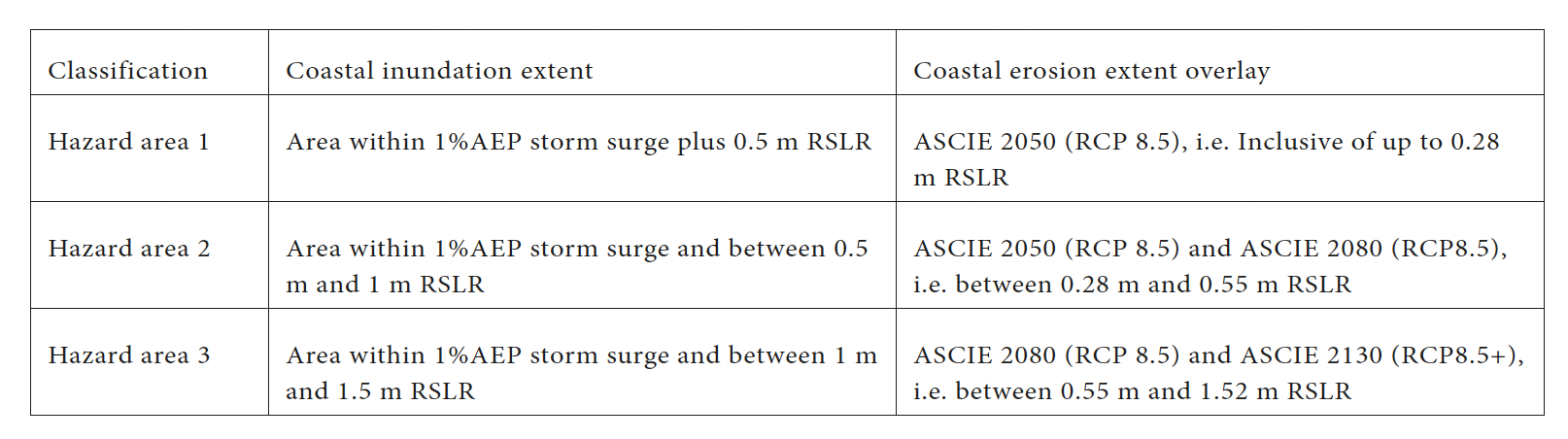

Natural hazard areas are identified by hazard type and the degree of exposure and include typical design events such as the 1% Annual Exceedance Probability (AEP). Hazard areas are assigned categories (i.e., high, medium, low or area 1, area 2, area 3) that are used to determine whether resource consents and site-specific assessments will be required depending on the type of activity that is proposed. Within those site-specific assessments, lower probability events, residual risks and the effectiveness and effects of mitigations are considered.

Table 1 shows an example of the hazard classification based on publicly available hazard information on Auckland Council’s GIS viewer. While region-wide policies and rules apply in all hazard areas, in coastal hazard Area 1 (as in very high flood risk areas) residential areas are proposed to be down-zoned to single-house zone to limit future intensification. Significantly, PC120 also uses a regional rule that requires a resource consent to rebuild if a building has been materially damaged or destroyed by a natural hazard event, something typically enabled as of right.

Table 1: Example of hazard classification based on coastal hazard overlays in Auckland Council’s GIS viewer.

New information was used for the landslide hazard overlays and flooding maps are continuing to be reviewed and updated following the 2023 Anniversary Weekend flooding. The mapping of coastal hazard extents relied on existing mapping.

As has become accepted practice, this mapping is held outside of the plan itself so that they can be kept current. This provided a cost-effective approach utilising the best available information without delaying the development of the plan change.

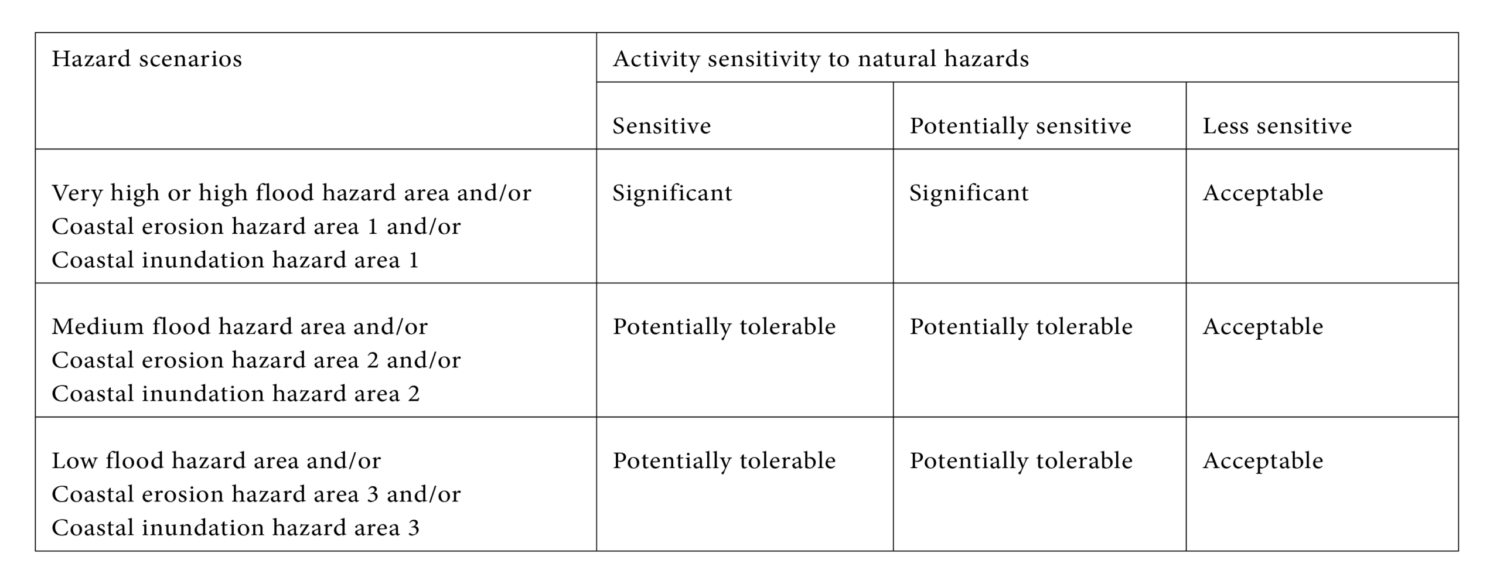

Activities are allocated a sensitivity rating of: ‘Sensitive’, ‘Potentially sensitive’, or ‘Less sensitive’ – which refers to the potential consequences should the activity be impacted by a natural hazard event.

Activities sensitive to natural hazards includes where people are regularly present and in a vulnerable state because they either sleep there, require medical treatment or require extra assistance during an evacuation (e.g., residential dwellings, healthcare facilities with overnight accommodation, hospitals) as well as activities which, if damaged, may create a significant public health or pollution issue (e.g., cemeteries, landfills, manufacturing). Potentially sensitive activities are those where people are present, but not usually in a vulnerable state (e.g., offices, retail, commercial).

Less sensitive activities are those with minimal presence of people and buildings and do not create public health or pollution issues (e.g., parks and public amenities, marine and port activities).

As shown in Table 2 below, risks are categorised as ‘Significant’, ‘Potentially tolerable’ and ‘Acceptable’ – based on the sensitivity of the activity and the hazard are category. Where risk is significant, the activity is to be avoided. In areas where the risk is potentially tolerable a risk assessment will be required to determine whether the risk can be reduced to, or maintained at, a tolerable level.

Table 2: Risk tolerance for subdivision, use and development within existing urbanised areas included in Draft PC120.

Outside existing urbanised areas both sensitive and potentially sensitive activities are considered a significant risk in all identified hazard areas, while less sensitive activities are acceptable.

Natural hazard risk-based land use planning is a practical and forward-looking tool that councils can use to reduce community exposure to natural hazards and support managed retreat where needed.

By identifying hazard areas, assessing the sensitivity of different land uses, and applying planning responses that are context-specific, local authorities can guide development to safer areas while making positive contributions to wider environmental, social and economic objectives.

Auckland Council’s Plan Change 120 demonstrates how this approach can be applied at scale, enabling growth around transport hubs while managing risks in hazard-prone areas. This provides clarity for decision-makers, developers, and communities, helping councils make informed, consistent, and cost-effective planning decisions.

Over time, it supports a strategic retreat from high-risk areas, builds resilience into future development and gets the most out of planned infrastructure investments.

For councils facing increasing climate/weather and hazard pressures, risk-based frameworks that respond proactively to potentially competing objectives are a key tool to balance risk, growth, and community well-being.

References

Archie, S. K. (2025). Strategic retreat: Balancing risk and societal goals in land-use planning. Environmental Science and Policy 163, 11.

Arnold, T. a. (2023). Report of the expert working group on managed retreat: a proposed system for Te Kekenga Rauora/Planned Relocation. Wellington: Ministry for the Environment.

Ministry for the Environment. (2024). Coastal hazards and climate change guidance. Wellington: Ministry for the Environment.

Natural Hazard Commission. (2021). Smarter Land Use Action Plan for Risk Reduction 2021-2026. Wellington: New Zealand Government.

Peart, R. B. (2023). Options and models for managed relocation policy. Auckland: Environmental Defence Society Incorporated.

Saunders, W. S. A.; Beban, J. G.; Kilvington, M. (2013). Risk-based approach to land use planning. GNS Science Miscellaneous Series 67. 97 p.

United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. (2015). Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030. United Nations.